Satellites are helping scientists discover more ancient Mayan ruins than ever before, no small feat considering how dense the forest is in the indigenous group’s ancestral lands.

“Archaeologists have mapped more Mayan sites, buildings and features in the last decade than we had in the last 150 years,” Brett Houk, professor of archeology at Texas Tech University, told attendees at a NASA-led conference about space archaeology. September 18 to which Space.com received an exclusive invitation.

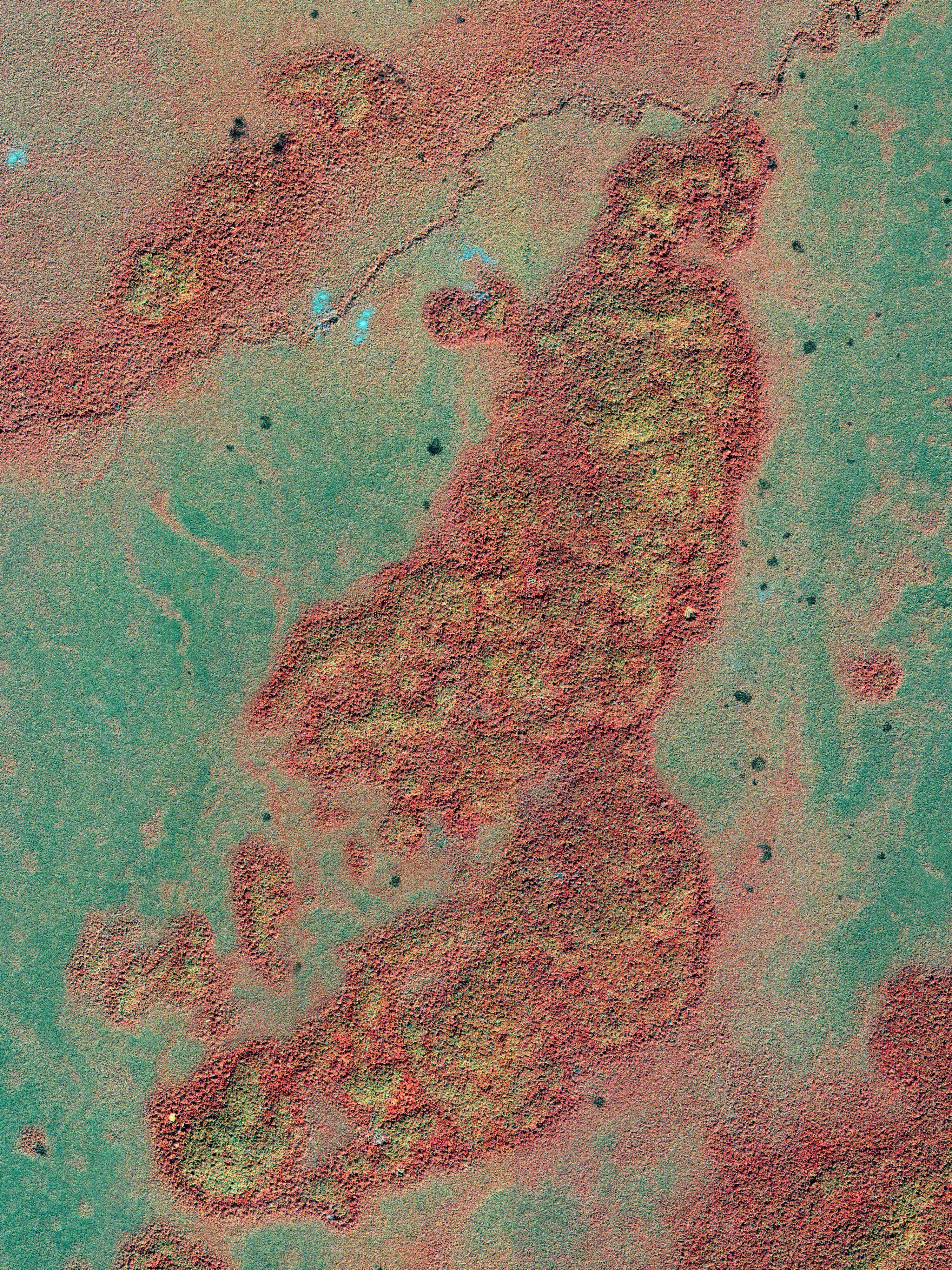

Archaeologists are finding these ruins faster thanks to better satellite technology. Using a pulsed laser technique called lidar, or light detection and ranging, satellites can see through the dense canopy around typical Mayan sites, Houk explained at NASA and Archeology From Space’s two-day livestream symposium.

Related: How satellites can protect archaeological sites vulnerable to climate change

According to Britannica, the Mayans are indigenous people whose ancestral lands include modern-day Mexico, Guatemala and northern Belize. Before the 16th century, when the Spanish invaded the area, the Maya were the dominant regional group. They created large pyramids and stone structures, managed agriculture and kept records using writing.

Mayan sites such as Chichén Itzá in Mexico are now marked as sites of important World Heritage by UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. But there are many more Mayan zones that have not yet been excavated and are even unknown to modern society, as their buildings were covered by heavy forest after the sites were abandoned.

Houk alluded to “new lidar missions” – their names currently under embargo as the team completes peer-reviewed publications – helping his team, whose work is co-led by Amy Thompson of the University of Texas. The satellites will help scientists locate more ruins in part of the permitted area in northeastern Belize.

The study covers a region about ten times the size of Manhattan: 650 square kilometers. It is rich in ruins. The team found 28 more monumental sites “in just a few days in the lab, staring at the data,” as Houk says, and plans to conduct excavations in some of these areas. For example, a study into canal and water management in the region is planned for next summer.

Mayan society changed not only under pressure from the Spanish, but also as a result of ongoing climate change, as far as numerous studies can show. Man-made global warming is one of the most pressing problems facing societies around the world today, leading to increasingly rapid flooding and extreme weather events; Investigating Mayan technology can therefore help ensure that the age-old ‘lessons learned’ are applied today.

“People and communities have adapted to changing environmental conditions and rainfall, designing a seemingly resilient mosaic of land use,” says Tim Murtha of the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, speaking about his own team’s independent space study of the Mayan technology. Examples included terraces for growing corn and watersheds for transporting and storing water in drought conditions.

Small satellites offer more opportunities to explore the Earth’s surface because they tend to fly closer to our planet; higher jobs require more fuel and money. Flyovers, or ‘revisits’ as the industry calls them, are therefore more common with a small cubesat than with a larger satellite that looks down at Earth from a slightly higher altitude.

Other presenters at the conference paid tribute to companies such as Planet Labs, which have provided Earth observations that are particularly valuable to archaeology. But the downside is the cost and access; scientists try to use open data or declassified satellite images whenever possible, as satellite companies also focus on making profits for their investors.

Artificial intelligence could play a role in spotting ruins in satellite images further down the line, but training and getting access to the right algorithms are also expensive problems, presenters said. They asked for more education and accessibility for future archaeological research.